Interview: Katherine Ball

We met artist and activist Katherine Ball when she lived in Copenhagen in the fall of 2010. Ball made us a worm-compost bin as a present/art piece before leaving the country on other adventures. I checked back in with her a year later to see what she was up to because of our mutual interest in issues of art, ecology, and activism and, to no one’s surprise, Ball has been busy. In fact, she barely had time to talk because she was occupied handing out homemade, vegan doughnuts to Portland, Oregon cops as part of the Occupy Wall Street actions happening in her home city.

The fact that she has only been back in Portland for a little while, after many months of travel and artist residencies and yet, she is already deeply involved in the issues of the Occupy movement, speaks to the commitment Ball has for political action. She is consistently looking for ways to change the world, whether through art, direct action, or long bike rides. Ball is open to all available options.

For this post, I am going to focus on Ball’s most recent project, an artist residency on Andrea Zittel’s Indianapolis Island at the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA). Zittel, a contemporary artist whose work focuses on day to day living, created the project to ‘bring into focus fundamental issues of need, comfort, security, and privacy.’ Zittel’s island is a 20-foot in diameter, fiberglass, and experimental living structure situated within IMA’s 100 Acres: The Virginia B. Fairbanks Art and Nature Park. The park includes woodlands, wetlands, and a 35-acre lake and is one of the largest museum art parks in the United States.

To participate in Indianapolis Island, artists propose projects, and one to two accepted projects are realized per summer over a six-week residency period. Ball was at the island from August 12-September 25, 2011. Her project, named for the warning sign placed near the lake, was titled No Swimming. She kept a blog about her work, experiences, and thoughts. In a letter she wrote to Zittel, on the blog, she said, “Living in your island has forced me to realize my curiosity for off-grid, autonomous living.”

The main focus of Ball’s work at the island residency was creating a better environment through systems design. While on the residency, she developed two systems based projects – mycofilters made from burlap, straw, and mushroom mycelium and a greywater kitchen sink system. The mycofilters were designed to lower E.coli levels in the lake. The greywater kitchen sink system was designed to streamline the wastewater from the island’s kitchen.

Ball learned that the residency lake, on which the island sat, was polluted–the reason the “No Swimming” was posted. She felt this was the perfect opportunity to try out what she had learned about bioremediation from fungi scientist Paul Stamets. She met Statmets as part of her cross-country bike tour researching solutions for dealing with climate change. Using his book Myclieum Running, Ball developed a plan for her own mycobooms to clean up the contaminated water. She spread the large, burlap, mushroom growing tubes around the lake and monitored them over the six-week period.

How the process works:

“Mycelium is the vegetative part of a fungus, consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. A mushroom is the fruit of a fungus. Paul refers to mycelium as a “grand recycler” and “nature’s internet” because mycelium absorbs nutrients from its environment, breaks down complicated nutrients into smaller building blocks for life, and transports them throughout the soil. Mycofiltration is the use of mycelium to filter water. A mycoboom is a type of mycofilter.”

For the greywater system project, Ball created an addition to the island’s pre-existing kitchen sink. Interested in closed looped systems, she felt the greywater sink was a way to synthesize this interest with what she was learning about mycelium filtration techniques. She describes the system she made here:

“The greywater system is designed with the intention that plants will transpire the [waster water] into the air, so I don’t have to deal with draining and dumping any effluent. The system’s mechanics are three tiered: I rerouted the sink in the island so it empties into a sink filled with boxes of straw, wood chips and corncobs inoculated with oyster mushroom mycelium, my hope is that the mycelium will clean the greywater enough so when it moves on to the third sink filled with plants, the plants will be happy to drink the water and transpire it into the air.”

Ball’s project on the Indianapolis Island is interesting not only because of the practical applications for the local environment, but also because of her willingness to openly express questions about the efficacy of her cultural work in conjunction with environmental activism. The No Swimming blog she created contains several musings from the artist about the intersection of politics and cultural work. For example, Ball is concerned about the ethics of working for the IMA, which is funded, in part, by pharmaceutical giant, Eli Lilly. She raises the question – How do artists practice responsible acceptance of funding, when their personal politics do not agree with the practices of the funding bodies they ultimately work for?

The artist posts her own questions next to quotes from some of her favorite thinkers, including UK-based, environmental activist, and artist, John Jordan. Quotes Ball selected from Jordan:

“How do we make radical politics as desirable as the next iPod? Because if we don’t go down that line of making radical politics speak to desire and aspiration, embedding the optimism embedded in consumption into our radical political acts–then I think we are really are heading for the end of the world.”

“The question of art is no longer aesthetics, but the survival of this planet.”

Overall, Ball’s artwork is a vehicle allowing her to connect with people about ideas of environmental sustainability and for her to work through her own thoughts on politics and culture. Ultimately, many people have made greywater systems before, but the finished product is not so much about the new kitchen sink system, but the thoughts that occurred and the discussions that were had along the way. Ball’s work is about an ongoing conversation with the world and it is a conversation I am interested in following.

Note: all images courtesy of Katherine Ball and the No Swimming project at the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

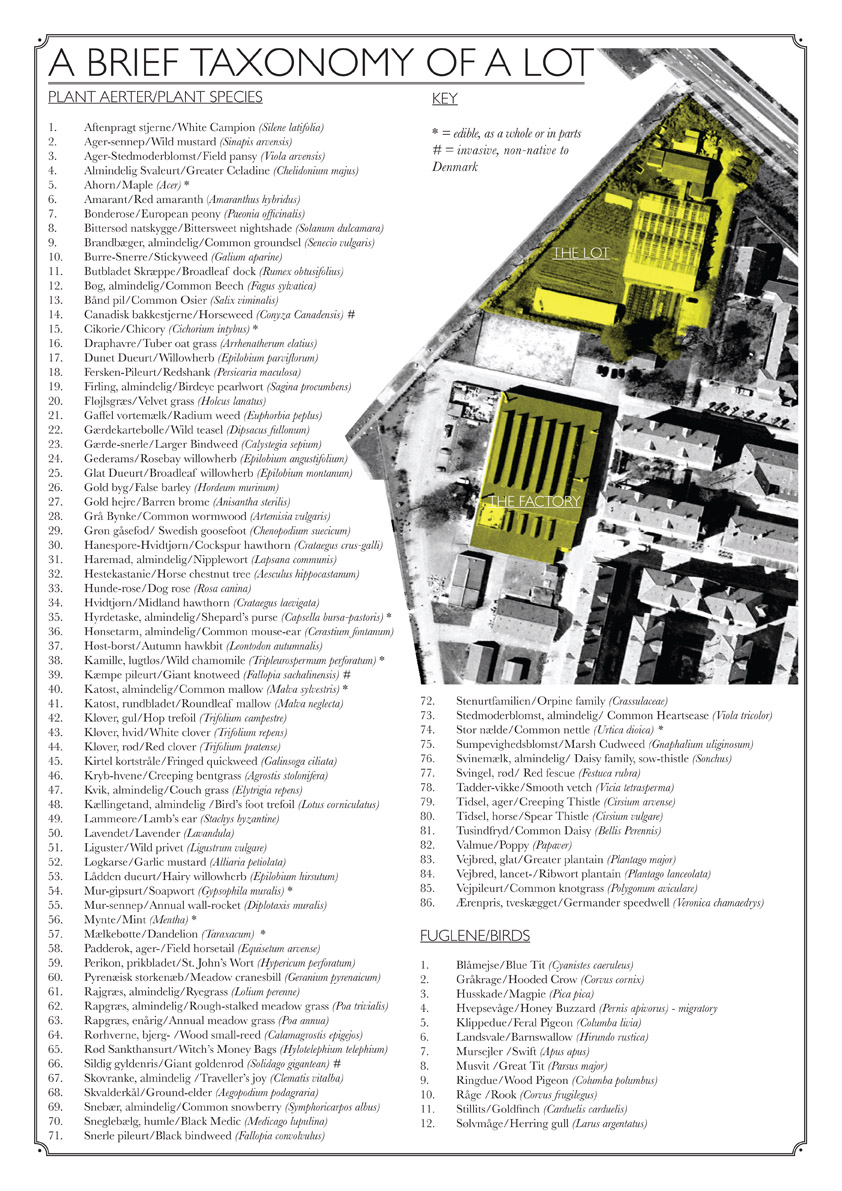

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

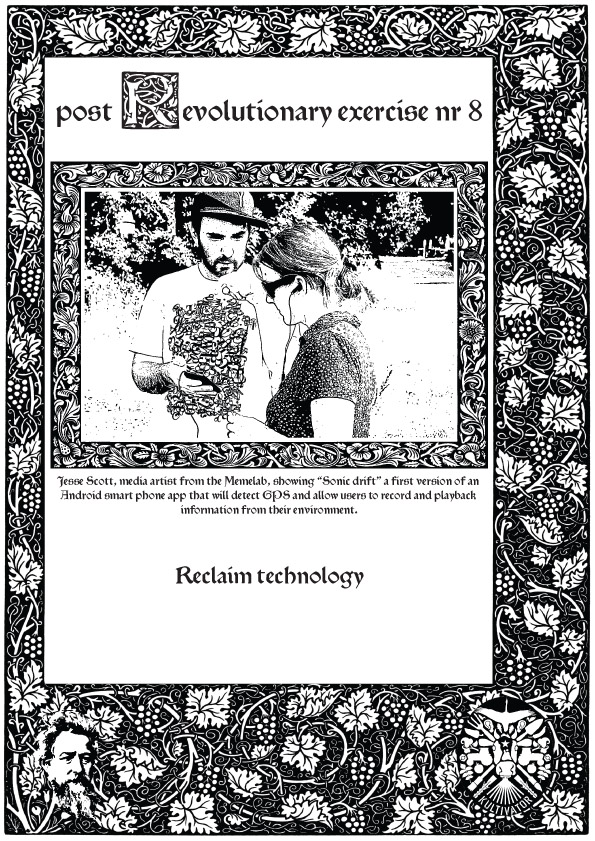

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

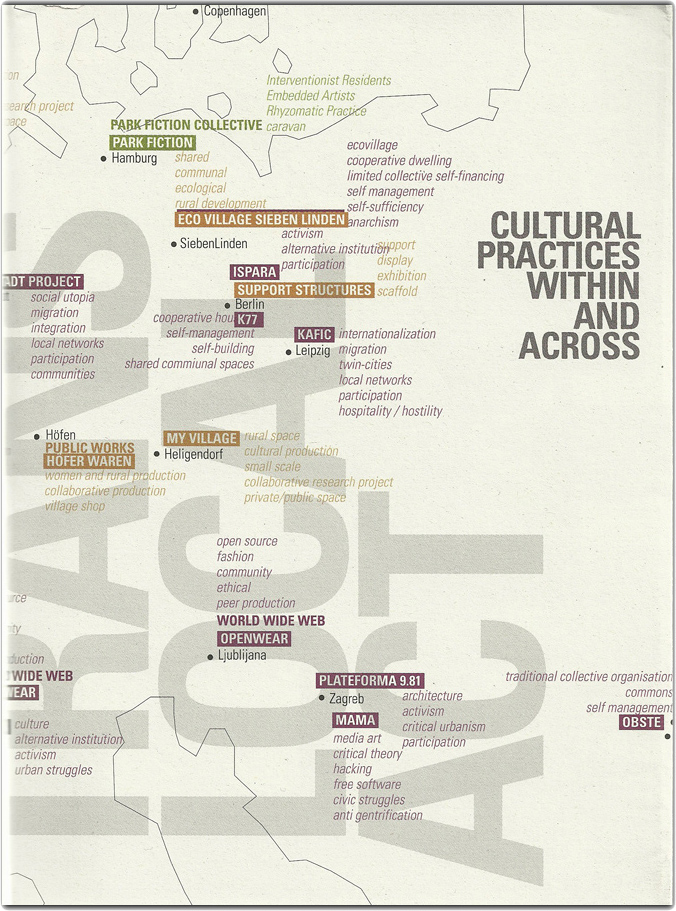

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.