Artist Parents: Matthew Friday

This post is the second in our series about Artist Parents

and the ways in which they maintain a creative practice while balancing

the labor of parenting. Each Artist Parent post will feature

information about what the artist is working on + comments that they

have about life as a parent.

“Experiments like this mandate a disposition of

conviviality, generosity and joyous risk that takes time to cultivate. When you

live from paycheck to paycheck, while taking care of aging parents and growing

children there isn’t much leeway for failure except for the slow soul-crushing

kind inherent to this system. I think parenting and in the broader sense

community interaction is exactly where we can begin training for this type of

new commons.”

-Matthew Friday

Artist Matthew Friday works in the collaborative group Spurse and is based in Kingston, New York. His specialties include: radical pedagogy, regional ecologies, the practices of communities of resistance, and human and non-human labor practices. He is the father of one. Friday has responded thoroughly and thoughtfully to our questions, so this post is a bit of a long one. Hope you enjoy and thanks again Matthew!

MQ: Tell us about yourself and your art practice.

I’m part of research collective known

as spurse (www.spurse.org)

that, among other things, critically examines ecosystemic relations and

develops new ways of being of the world. I’m incredibly fortunate that many of

my colleagues in spurse are parents who are open to and interested in ways we

might involve our families. For the past year, we’ve been developing a project

called “Eat Your Sidewalk” which started as a series of non-stop, seven-day

urban festivals that challenge communities to eat and live on what they can

glean, hunt or pick from their streets. The goal of these immersive events is

to change our sense of food, and become more sensitive to all that surrounds us

(plants, food, materials, waste, kindness, communities, and our fellow

critters). Imagine a mash up of a locavore cooking competition, foraging

workshop and community advocacy meeting that tries to combine some of the

tactics and ethics of the occupy and the slow food movements. After a

successful Kickstarter campaign we’ve moved on to completing a book based upon

these experiments and expect to have it published within the next few months.

For me, a big part of this research has involved gardening and foraging with my

daughter and our neighborhood rambles have afforded me the possibility of

connecting with all sorts of interesting people, groups and critters. I was

especially excited to collaborate with the Riverkeepers one of the most successful activist organizations involved with environmental

issues, their amazing track record of successful legislation, watershed reform

and educational campaigning has really been an inspiration for what engaged

social practice could look like.

MQ: Can you give us more details about the ways in which you are working together with the Riverkeepers?

Since

moving to Kingston, New York a little over two years ago, I’ve been researching

the political ecology of water within the Hudson Valley region. It’s something

of a public secret that New York City has the largest and cleanest unfiltered

water system in America of which approximately 70% comes from the Ashokan

reservoir that lies just outside of Kingston. This reservoir is threatened by

proposed hydro-fracturing gas mining, industrial pollution and changes brought

by climate change. The Riverkeepers have been at the forefront of political

action concerning watershed issues in the region and their impressive ability

to combine activism, legislation, education and enjoyment initially drew me to

them. I’ve met several times with their regional project leaders who have

served as important conduits to other activists, scientists and concerned

citizens. The Riverkeepers have generously made their water monitoring data available to me and I joined their citizen scientist program to learn how to do my own water testing. I’m working on publishing a large map of the political ecology of the Hudson River Valley watershed that draws heavily from the research the Riverkeepers have done. I’d have to say that working with the Riverkeepers has been one of the most engaging, open and reciprocal collaborations I’ve participated in.

MQ: Tell us about how you balance your day job as an arts educator, your art practice, and parenting. Where do you find support or the lack of support?

As an administrator and professor at a state school I’m

expected to be continually available. Rarely am I consulted about either my

teaching schedule or my meetings and they are made with little concern as to

how they affect my parenting. Let me give you a concrete example.

Against my protestations, I was elected to serve on our

merit, promotion and tenure committee this semester. Part of my recalcitrance

had to do with the knowledge that I’d have to attend numerous meetings outside

of my normal work schedule. So as not to take away from our required class time

we were instructed to meet on a Saturday and Sunday for what amounted to

eighteen hours of continuous work. I typically handle child-care over the

weekend freeing my wife up to work, so this schedule necessitated hiring a

baby-sitter at the last minute. I don’t see my daughter much during the week

and this particular weekend I was only able to spend breakfast with her as I

hurried off to work.

The institutional structure of academia and the art world will

allow you to make work about your family, but not for your family. I can take

my daughter on mushroom hunts, create a neighborhood compost pile and attend

field trips with the Riverkeepers, but unless these solidify into some form of

acceptable exhibition and/or publication they will be dismissed as amateurish,

lacking skill, creativity or criticality.

I know to some I must sound like a

whining, over-privileged academic. After all don’t most people have it worse?

Yes, they do. But saying so simply justifies a system of deep-seated

inequalities (sexism, racism, classism, etc.), externalized labor and shitty

parenting. Growing up in a family with deep ties to the labor movement, I

always thought solidarity meant something that occurred primarily across class

lines and usually in the work place. Parenting, more than any experience, has

taught me that this isn’t enough.

An authentic relation to parenting, at least for me, means

first redefining some of the preconceived assumptions mobilized by the term “artist.”

Artists make work for art places and art audiences and they frequently make

that stuff alone or, if they’re successful, they hire a bunch of people to make

it for them. Artists are thought to be innately talented, creative or, more

recently, critical. But that is a long conversation and what seems important to

me is that all of these options foreclose the opportunity of including my

family as an equal partner. I’m wondering how do I redefine the boundaries of

my practice? Where/when is the studio? In the broadest sense, what skills do I

need? How can I find ways to collaborate with my and other families? What sort

of generosity and imagination would be called for to actually make work for/of my family? What sort of networks or affiliation can I enter into that will support this? Who the hell is going to be interested in this sort of thing?

Before attending primary school my parents sent me to a daycare co-op where instead of money, time, was the currency of exchange. Working class families who could not afford expensive Montessori or Waldorf pre-schools donated a day a week so that their kids could be watched by other parents and play with other children. Parents formed local reading groups, adopted what they found useful and formed their own educational commons. It is a measure of how far capitalism has colonized my mind that makes this seem inconceivable, if not impossible. Aside from occasional visits from relatives and a functional but expensive day-care necessitated by our work schedules, my wife and I do our parenting alone. I can’t help but feel like something has been lost, an opportunity for conversation, play and communal imagination.

MQ: You write about parenting alone in contrast to a

community of organized parents, and your complicated work situation in contrast

to a family history with the labor movement. In each instance you seem to

suggest that this is not how you imagined your adult life would be…what do you

think it would take/what could you/government/communities do to make a world

more like the one you imagined?

As I read this question, I’m reminded of how hard it

is to even envision a different model of parenting and familial relations. Were

it not for my parents’ participation in communal childcare, the horizon of my

imagination would be even more impoverished. Power always tries to represent

itself as the path of necessity and I wonder what other possibilities we have

become blind to as our lives become ever more thoroughly dominated by market

forces.

First and foremost, I think we need the space to experiment, to

collectively take pleasure and find mutual affiliations in our parenting. On a

governmental level basic things like healthcare, decent maternity and paternity

leave, subsidized childcare and support for community groups would constitute a

good starting point. But let’s not stop there! What if these groups had the

power to create their own organization structure, author legislation and

directly access public funding? Imagine if a group of parents were given

funding, staff and materials to create a public garden and organize their own

education program based on ecological research? What if political issues

emerged from these groups, rather than from the hierarchical imposition by “political”

parties fully beholden to corporate interests? What if instead of rewarding

research disseminated only through elite market venues, academia and the art

market focused on scales of affect and transformation? This would necessitate a

dramatic re-evaluation of the role and responsibility of cultural production;

questions about sustainability, not simply in limited sense of financial success,

would need to be considered. On the surface, this seems possible, but the

entire legal, cultural and economic apparatus is mobilized to make sure that exactly this type of thing does not happen.

Experiments like this mandate a disposition of

conviviality, generosity and joyous risk that takes time to cultivate. When you

live from paycheck to paycheck, while taking care of aging parents and growing

children there isn’t much leeway for failure except for the slow soul-crushing

kind inherent to this system. I think parenting and in the broader sense

community interaction is exactly where we can begin training for this type of

new commons. Small acts have a way of accumulating and in time can push a

system over a threshold forcing a new set of actors and relations. I’ve found

that the simple act of occasionally volunteering to lead a children’s workshop

at a local nature center can have profound consequences and lead to an expanded

and more active community.

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

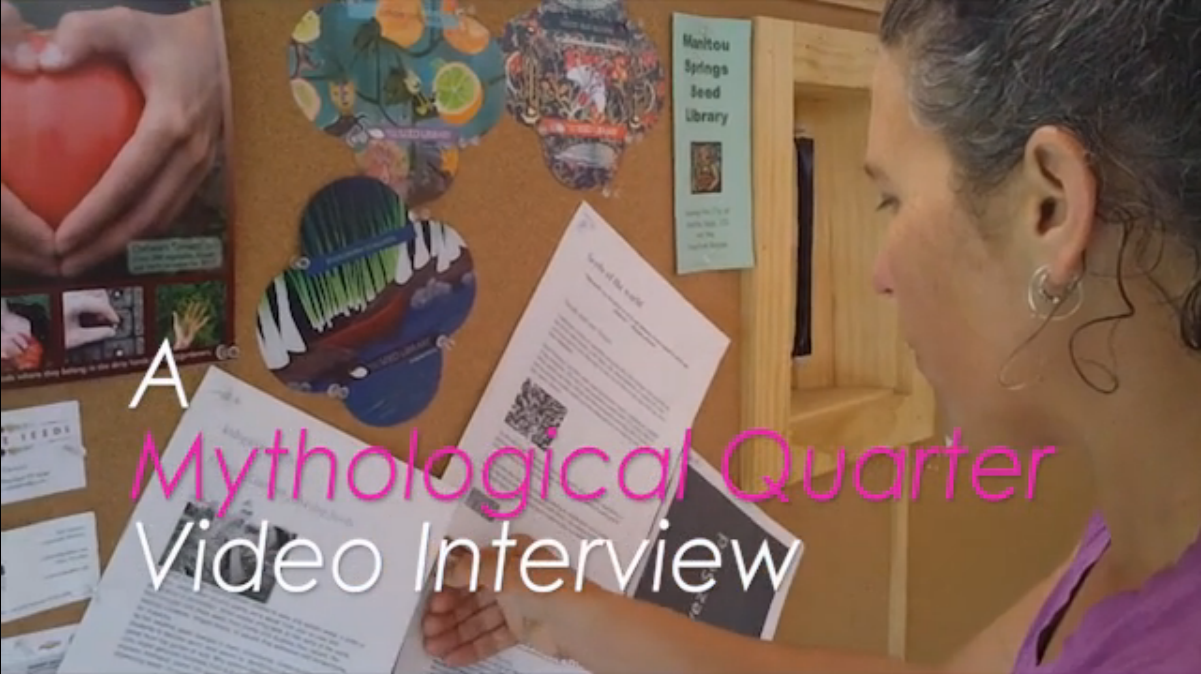

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

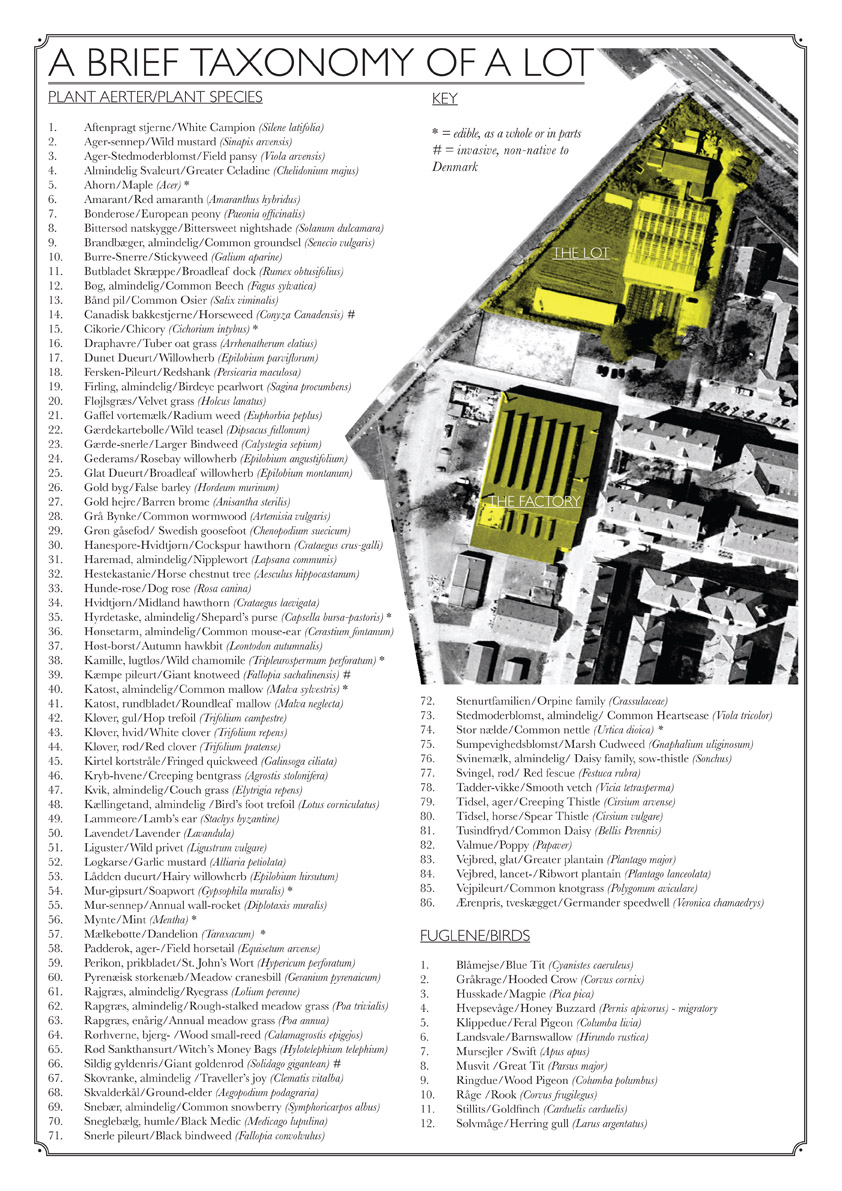

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

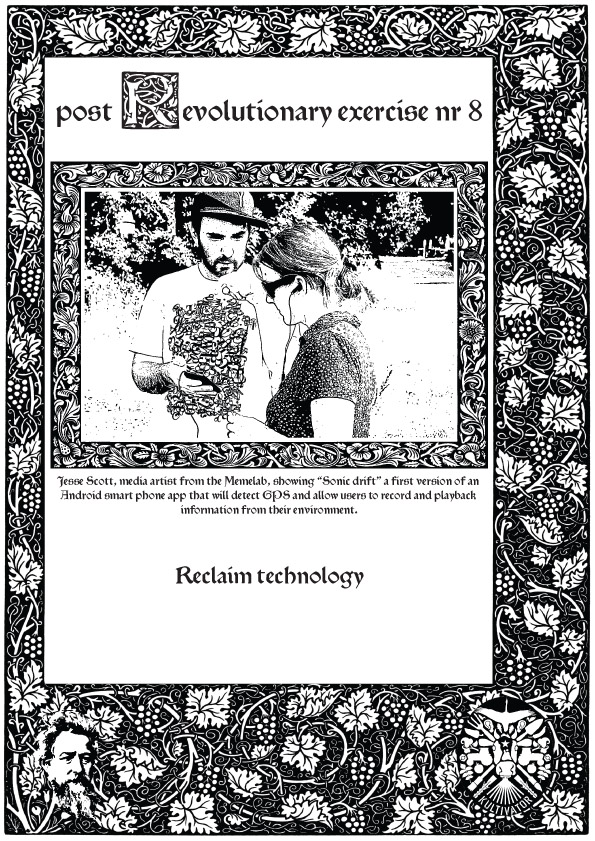

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

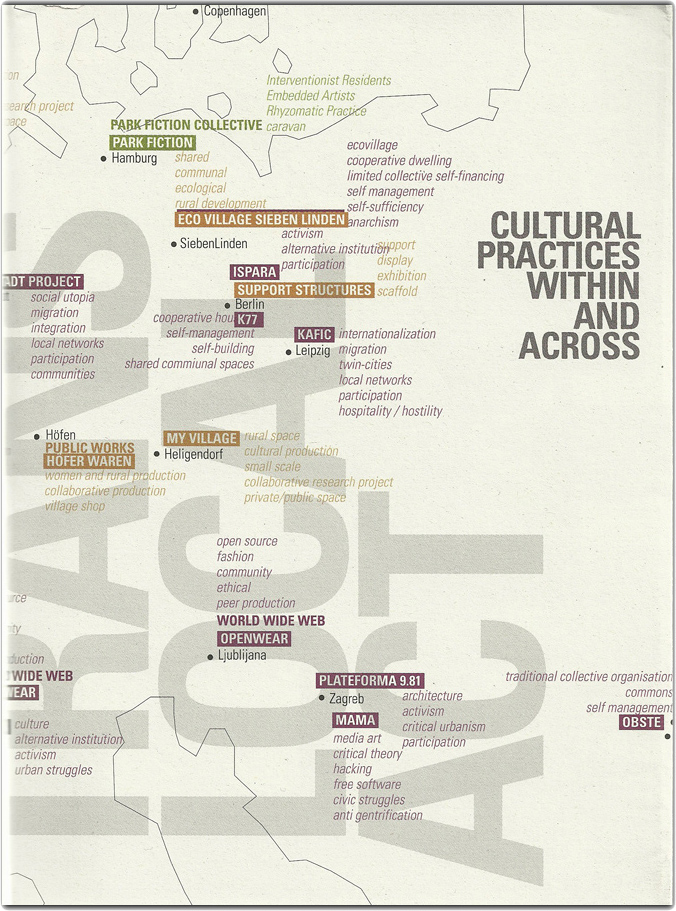

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.