Book Review: Land, Art

The book Land, Art: A Cultural Ecology Handbook is out of print. Edited by Max Andrews and released in 2006, the book was part of the enviable Art & Ecology series initiated by The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce (RSA) in partnership with Arts Council England. The series, which lasted from 2005-2010 used to have a website, but that has since be taken offline. Though there is no longer a main website but a collection of short films commissioned for the program, called “Stop. Watch.” still remains online for viewing. You can see them here.

We borrowed a copy from our friends at Learning Site, who are included in the book (with a project Brett from MQ worked on when he was a part of the group), so we could review it here for our readers. To that end, we are also sharing several images to communicate a few projects and the overall book design, because how else are you going to be able to see it since the only available copies are around $400 (WTF?!).

The RSA Arts & Ecology program was an arts and culture “open research” initiative, lead by Michaela Crimmin then head of RSA. Crimmin, an independent curator, is interested in art that seeks to make a social impact. The program created a series of artist residencies, commissions, and lectures to publicly explore the implications of climate change on the environment. The goal was to promote public discussion and new artistic investigation into environmental art, while hopefully developing alternative futures. Crimmin has discussed her thoughts on the role of artists as leaders in cross-disciplinary discussions on issues of climate change here. Following the Arts & Ecology series, Crimmin moved on to work on issues of “human rights, conflict and migration” what she calls the “tough end of climate change” with the Culture & Conflict program. Read more here.

Now on to some selections from Land, Art: A Cultural Ecology Handbook.

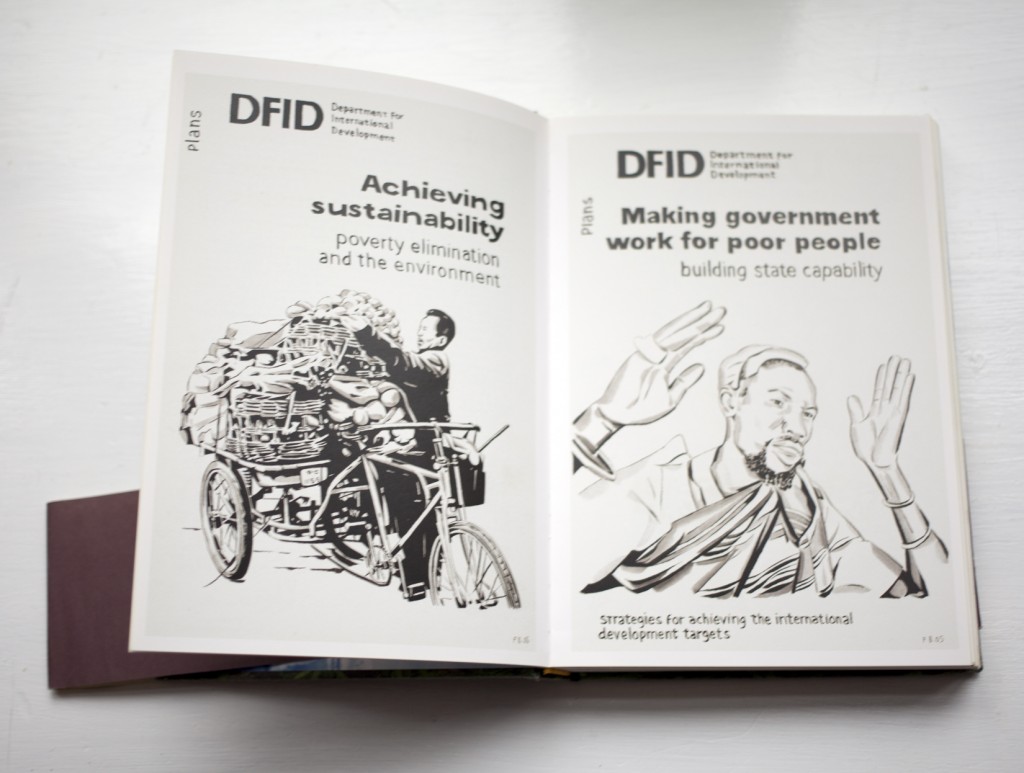

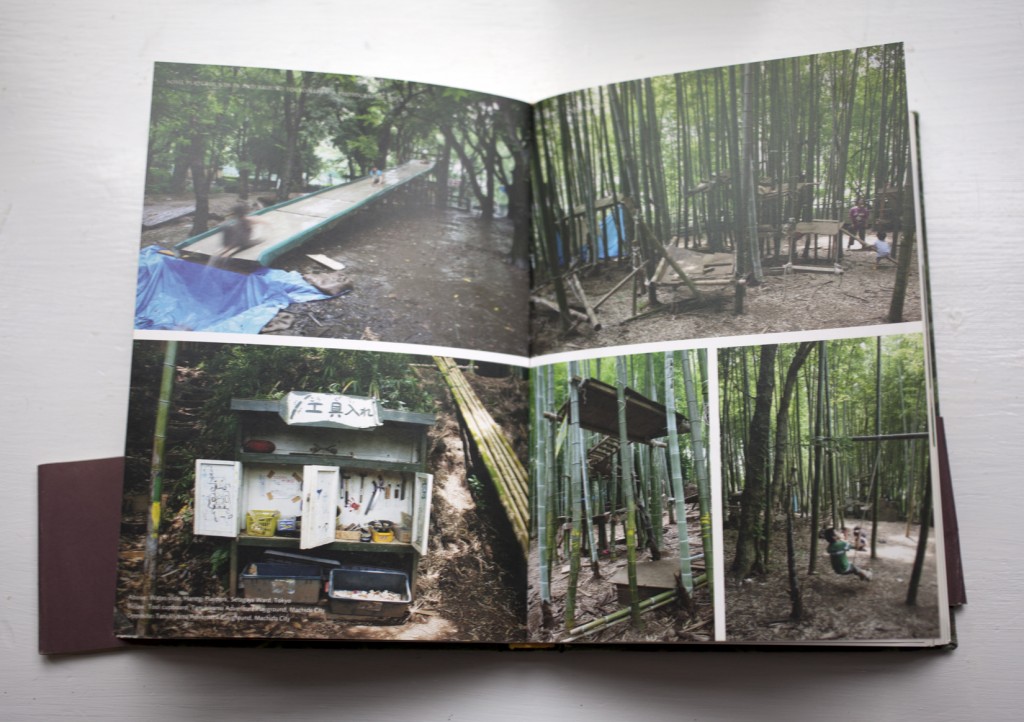

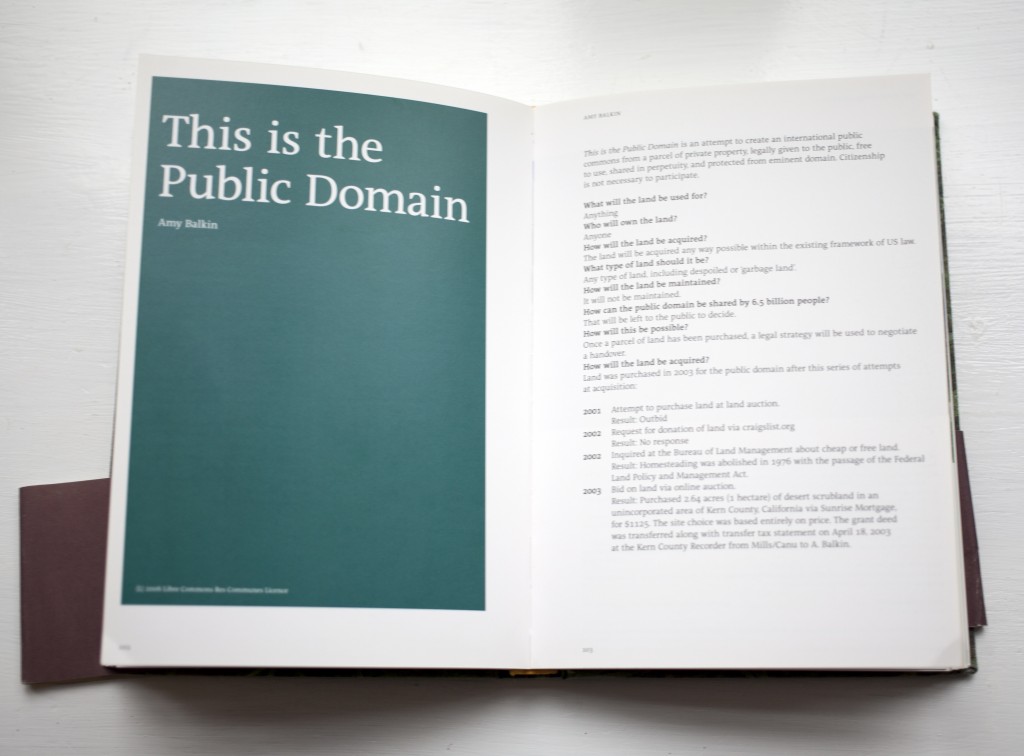

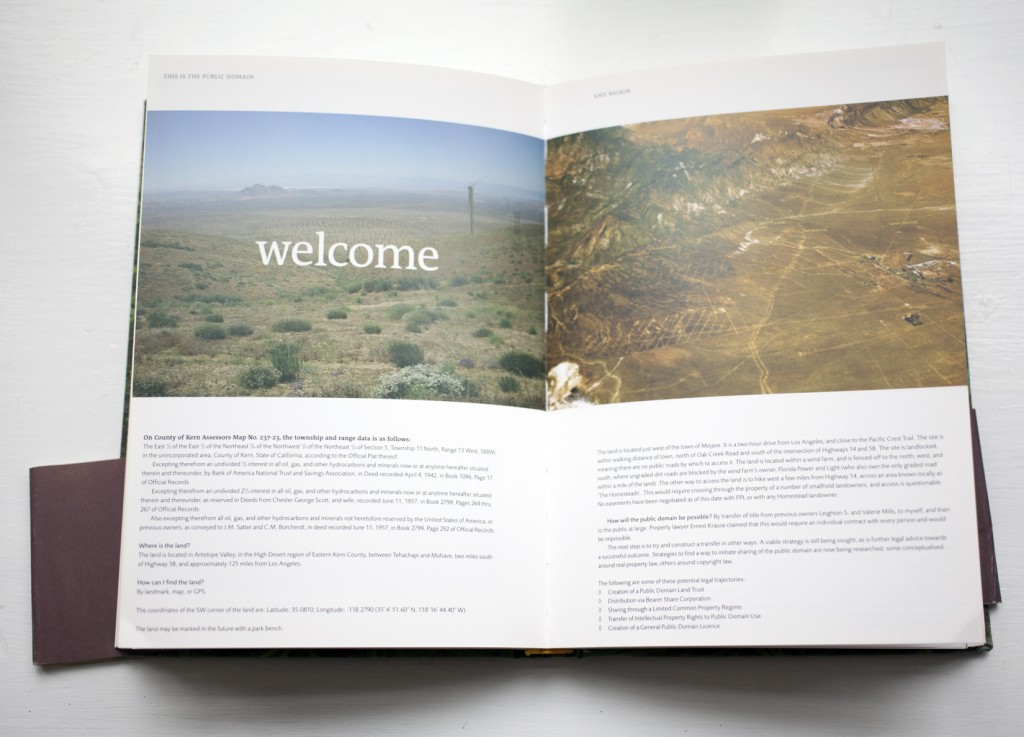

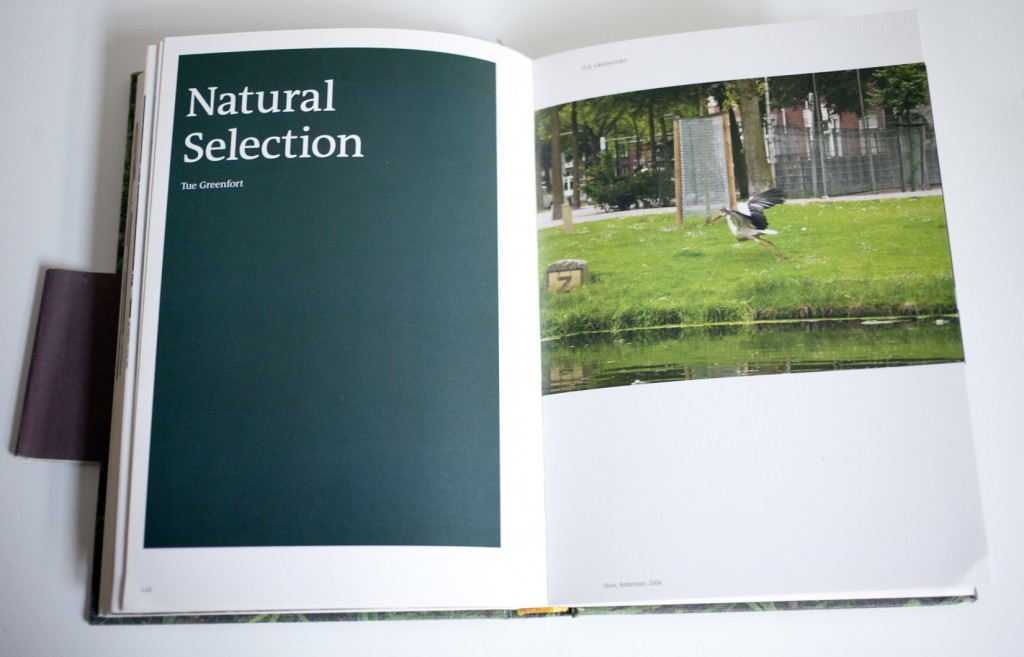

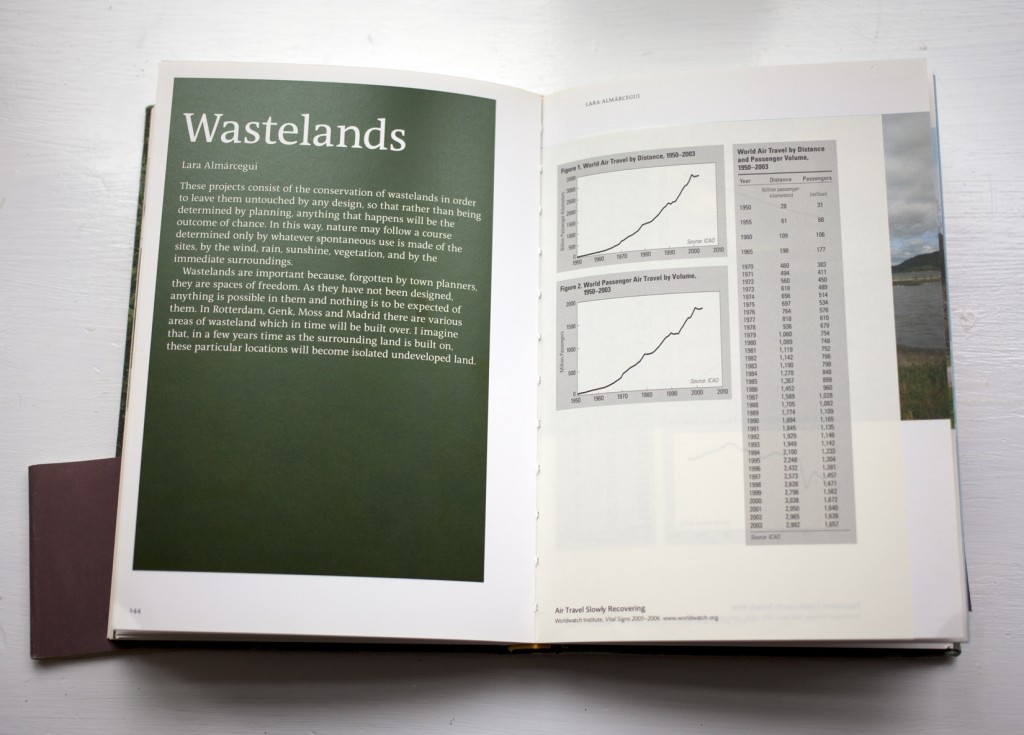

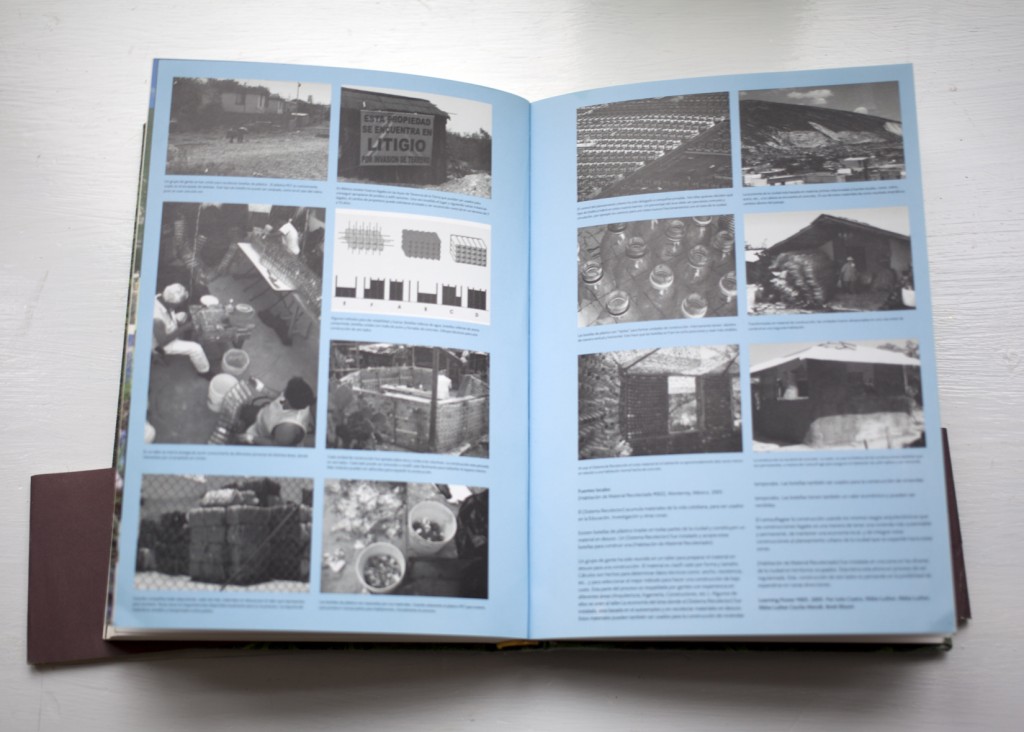

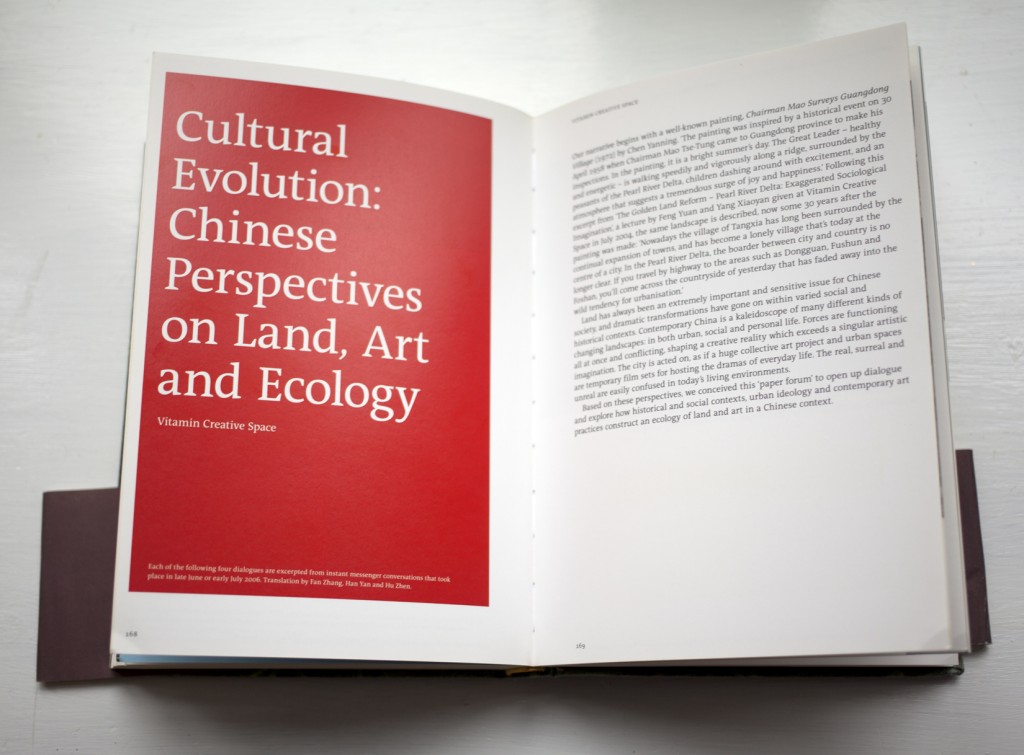

Fernado Bryce, from Work in progress, 2005-06. Ink on paper, series of 80 drawings, 29.7 x 21 cm. / Nils Norman, “Some Playgrounds in and around Tokyo, Japan: A Photographic Tour.”/ Amy Balkin, “This is Public Domain.”/ Tue Greenfort, “Natural Selection.” / Futurefarmers and Free Soil, “Two Interviews: Artist-as-Citizen/Scientist-as-Citizen: Futurefarmers interviews Johnathan Meuser.”/ Lara Almárcegui, ” Wastelands.” / Learning Group, ” Information about [Collecting System] in Monterrey, Mexico / Vitamin Creative Space, “Cultural Evolution: Chinese Perspectives on Land, Art, and Ecology.”

—

Lucy Lippard writes in her introductory text to Land, Art that, “the land itself, how we see, understand, use, and respond to it” is the key for discussions around climate and the environment going forward. Max Andrews further clarifies the book’s focus: land. He acknowledges an art historical time line moving from 1960s and 70s Land art to present day practices involved with the environment but specifying that this collection of essays and projects is about the intersection of land, art, and the environmental movement. The book combines images with writing and interviews from cultural and scientific workers, as well as environmental activists like Winona LaDuke and Wangari Maathai.

One of my favorite pieces documented in the book is Amy Balkin’s This is Public Domain. Balkin discusses the human impact on the landscape in her work. With this piece she uses legal procedures to first purchase a piece of land in Kern County, California, and then to try and return it to the public domain so that it can not be built upon or extracted from. The documenting text describes the artist’s investigations into property and copyright law to determine the legality of setting the land aside as public domain in perpetuity.

A related piece is Lara Almárcegui’s Wastelands—a collection of photographs documenting wastelands in the Netherlands, Spain, and Belgium. Her wastelands are small plots of land in industrial areas. In her opening text, the artist writes that wastelands are important as ignored and interstitial spaces that by virtue of their abandoned quality make excellent sites for wild nature to follow its course. Unfortunately, from the book documentation it is unclear weather the artist was able to secure legal rights to allow these “wastelands” to remain permanently untouched, knowledge which would make an excellent counter to Balkin’s land piece.

A final piece in the book in relationship to the purchase of land—Paul Schmelzer’s interview with Native American and environmental activist, Winona LaDuke. LaDuke founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project to reclaim tribal land of the Anishinaabeg of northwestern Minnesota. With her organization, she buys back land to rejuvenate local economic and social infrastructure. In her interview, she brings up the Ojibwe phrase omaa akiing, which she describes as meaning to be part of the land, to take care of it. It is associated with responsibility to the land and one’s community and she argues it is a very different way of relating to the land than via a Western legal framework that sees the landscape as a resource from which to extract.

Land, Art is an excellent interdisciplinary survey of practices and modes of thinking in association with the landscape. Find a copy, if you can, and check it out.

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

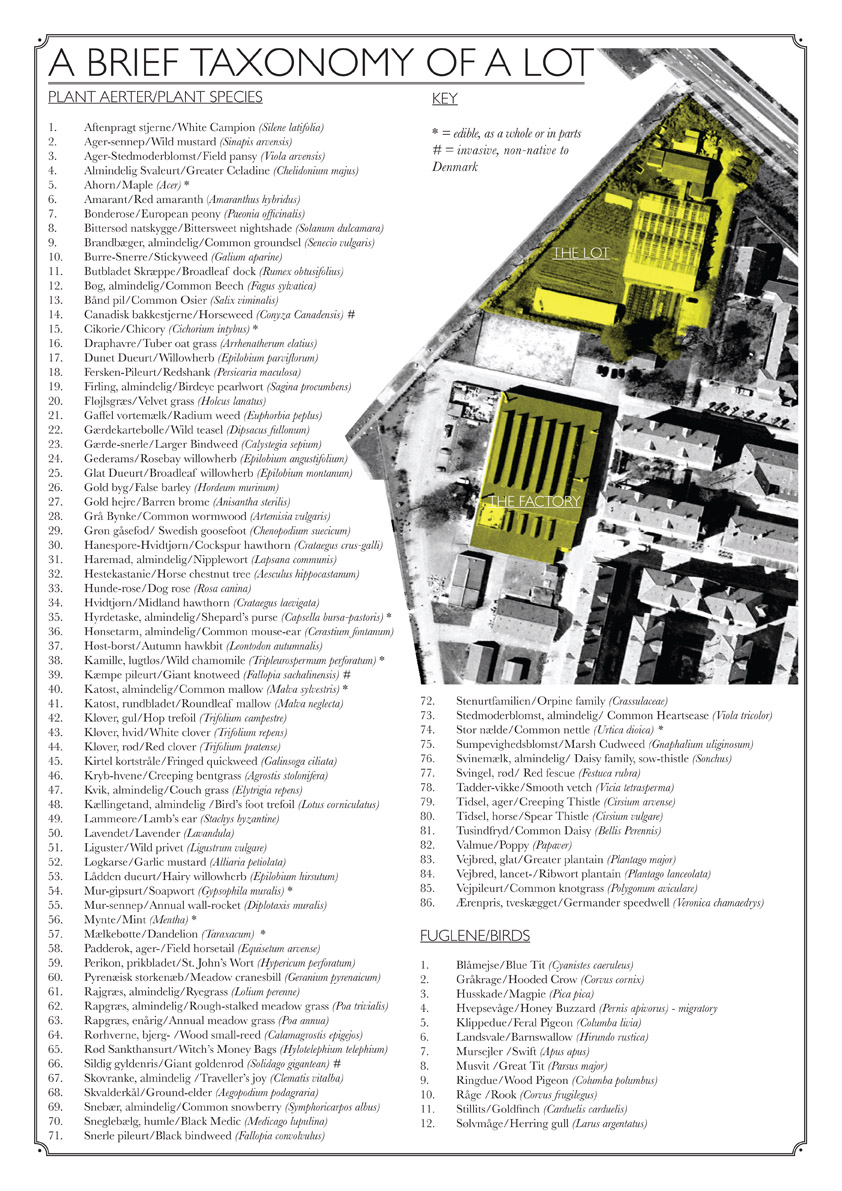

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

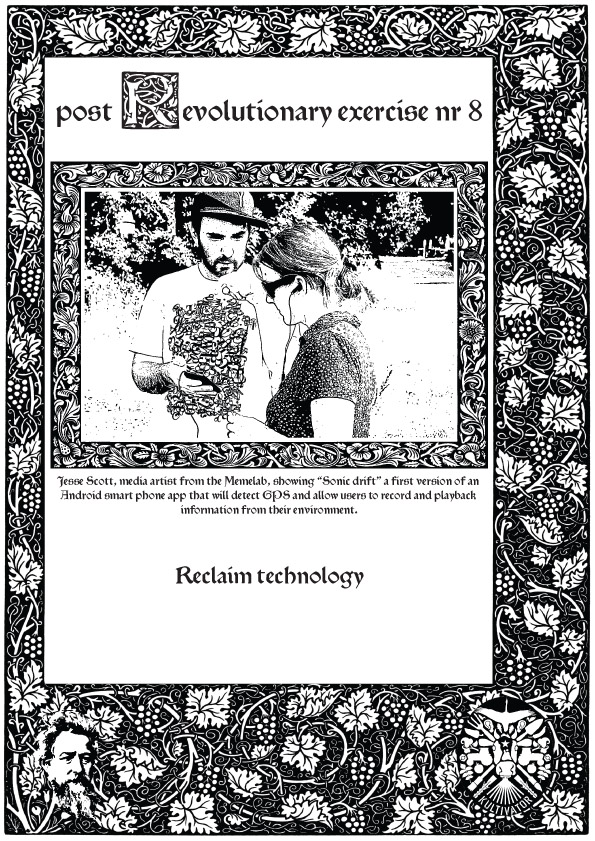

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

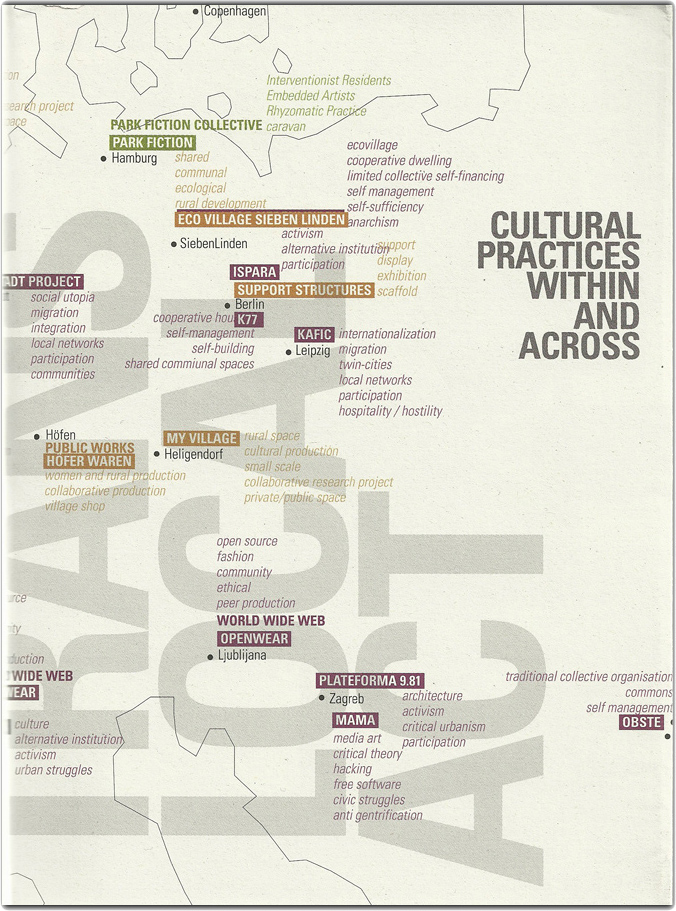

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.