Learning carefully from the sea, its vast silences & ancient stories

I recently conducted a two-day workshop in Helsinki, on two different islands in the Baltic sea, with 10 participants. The workshop was coordinated with the exhibition Dissolving Frontiers, one of many exhibitions, incubators, projects, and more that are part of Frontiers in Retreat, an ambitious 5-year initiative that partners 7 artist residency spaces “on the frontiers of Europe” with over 20 artists working at the intersections of art, ecology, and climate change. The workshop was about de-industrializing one’s understanding of self and place towards a more embodied sense of the world and an urgency to build different kinds of relationships. One hope I have is to work with others to start articulating cultural formations that will help us survive whatever chaos and destruction is coming our way with global climate change and increasing income inequality (click here for more about the workshop). In the workshops we did various kinds of exercises together and then discussed them. The exercises are about realizing one’s incredible capacities for both experiencing the world and the opening up to very unfamiliar and uncommon interpretations of what it is one encounters. This comes without prompting and people interpret their direct encounters with every day stimulus—like bird sounds, wind blowing through trees, vast landscapes—in really unexpected ways.

An exercise that we were doing, that I want to share here, was inspired by combining listening instructions from a couple of people who have done pioneering work around listening, sound, and thinking about how we can be more fully in the world. First, the composer Pauline Oliveros and her ideas of Deep Listening have had a big impact on the exercises I conduct. Deep Listening is listening with our full range of capacities and not just our ears, paying attention to all the sounds we hear at once, how they interrelate, how they hit our bodies and are registered in unexpected ways, and so on. Specific to this exercise, was work by the acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton—author of One Square Inch of Silence—to preserve natural silence and combat noise pollution in national and state parks in the United States. Hempton has spent decades listening to and making recordings of landscapes. He has some powerful things to say about how to refine and pay attention to our incredible senses, hearing, as he says entire landscapes at one time. Our task was to listen to the Baltic Sea, to the 30-50 square kilometers that were in front of us as we sat on a stormy, rock lined coast. Not only were we going to listen to this enormous space, we were going to try and listen to its silences instead of its noises.

We went to a spot on the shoreline of the island. I gave instructions to everyone to look at the vast distances we could see from our vantage point. Participants were asked to think about all the silences that were there to make it possible for one to understand what it was we were seeing, hearing, and experiencing. There was a light house on a small island we could see a couple of kilometers off the shore. I asked everyone to think about a firework being set off next to the light house. We would quickly hear the sound locating it without effort. We would instantly understand the distance, the silence that the lighthouse had been enveloped in just moments before, and all the silences around that remained in order for us to locate this one sound. The sound would occur for us both in the moment, but also in the context of its very recent past and future silences. We are always hearing the silences when we hear sounds; we just don’t realize this and pay attention accordingly. And our perceptions of time are extremely elastic too. Many participants in the workshop exercises talked about stepping out of time, or at least time as they usually conceptualize and experience it.

We had an interesting time trying to listen to the silences in the land and seascape because of the day’s strong wind and sporadic spats of rain. The wind had an immense presence, feeling very much like it does when a throng of people push you onto an overly crowded subway car. It was even more of a confrontation as we had only a short time before completed an exercise that sensitized us to how we gather sounds, how they hit our bodies in many more places than just our ears, and the enormous range and layers of things we are able to perceive when we take the time to listen deeply. We were all a bit cautious about how intensely the wind was insinuating itself in our awareness; the strong wind rattled and rasped our ears turning them into an active part of the soundscape. The wind itself is completely silent. It is only when it crashes into and careens around things that it triggers an audible trail of its presence. This was certainly the situation as the wind grabbed the sea and threw it repeatedly at the rocky sea shore.

We were on the shoreline of the island of Suomenlinna—an old military base and UNESCO World Heritage site—that is part natural formation and part massive land fill. It is an odd place filled with stables, barracks, bunkers, canons from multiple military epochs of technology, museums, churches, harbors, and more. The image above shows bunkers disguised as hillocks. There are many more of them and they line the shore facing the open Baltic Sea.

We stumbled down one of those staircases you often find in large outdoor parks where the angle of descent is awkward and the spaces between steps are not scaled for a normal human adult. Add to this the harsh sea weather, which has had its way with this stair case, turning it green in places, causing plant life to settle in in others. The stairs descended from an old fortification wall down to the place where we were headed to do our listening, to learn something from the sea.

The workshop participants were eager to do another listening session, to test their new found awareness on a completely different situation, as the first one provided such strong and varied responses. We all had heard the same things, or so we thought, but the narratives of what we each had heard, what we thought it was, the emotional impact it had, prompted really different understandings. There were some agreements amongst the listeners about what they had heard or how the impact of a sound—the loud voices of two drunk men shouting at each other for example—had registered on their senses, but what to make out of it afterwards and in conjunction with the entire experience was very different for each person. The same thing happened during this exercise.

We sat on rocky outcroppings close to the wall of sound that was by now pummeling all of us. The sun was teasing us with its continual presence and disappearance providing us additional stimulus to reflect on how warming and cooling of our bodies impacted our hearing, almost warming the very act of hearing for some, making others more receptive, they said, to what it was they were going through. We found our places on the rocks, some closer to the crashing waves than others, sitting, working ourselves into an intimate connection between our bodies and the hard surface, getting ready to listen. We breathed deeply filling our lungs fully and then emptying them utterly, relaxing our bodies until we felt all muscles release their tension and settle into the task. We were ready to pay careful attention. Because of the intensity of the wind and water, it took very little time to get lost in the phenomenal encounter. It was already difficult to talk as I gave instructions on getting into a relaxed state and the task of reflecting on the silences of the seascape. Upon closing my eyes, the vast spaces that had been there moments before rushed onto my body, ears, hands, my rather unprepared consciousness.

Several of the participants said after that they had to turn away because of the intensity of the wind and sound. When we talked after listening for about 30 minutes, many of us had very similar understandings of what we had encountered. We had all heard a very powerful story from the sea. This is very important to understand. Things tell us stories, not in the sense that a rock starts speaking English or Finnish or any other human language. But, we nonetheless construct narratives instantaneously out of what it is we observe and understand. I will write more about this in a coming essay about the fundamental metaphoric and narrative nature of observing anything whether listening, viewing or sensing in some other capacity, and the need to retransmit understanding to others. No matter how romantic, detached, analytical, mystical, skeptical, and so on, you might be, you have to construct a story of your experience. You translate the sounds of the wind and water hitting the rocks into first your own understanding, which will defy adequate words of description. You will then have to tell that story to others. Water hitting rocks smoothed by thousands of years of pounding from the sea sounds different than any other thing you will ever experience. We register this and attempt to communicate it to others.

The sea has a story to tell. It is a story that it has been telling for thousands of years. It can tell it in many different ways. The same spot on a shoreline can tell this story in an infinite number of variations given what the wind is like, the direction it is blowing in, the air temperature, whether it is raining or not, and so on. What we heard was the sound of many waves crashing against the smoothed rocks. These rocks have been shaped by this process. We know from encountering rocks countless times before that this is no easy task. It would be nearly impossible for us to recreate the same process just with our bodies and no tools even if we did it for decades on end. We understand what a rock is in a fully bodily way as much as we do a conceptual manner, though we are taught to privilege the latter understanding over the former.

We had heard a powerful thing during this short session. The sea was talking to us. Part of the story it had to tell was that it had been telling this story for a time that we are not really used to registering, deep time, time that extends beyond many generations of human life spans. The sea was telling us that its story has been uninterrupted for this long period. What you hear at first are the waves crashing on the rocks, and this is familiar to anyone who has been to the sea. When you pay attention closely, you start to hear the many tones, patterns, flows of energy that overlap, sometimes complement one another. They all combine to tell the story of the relationships of the sea to the rocks making them intimate and more available to us. The crashes of the waves on the rocks, the pulling back of the sea, that wonderful crackling noise it makes, were happening all around us in multiple variations. Because we had been sensitized by listening carefully, we could hold them all in our heads and interrelate them. What you hear is incredible, the multiple patterns that sync and at times produce pleasureful or jarring dissonance.

Many of us felt that we were sitting on the edge of a crushing abyss. The way in which we were listening pulled the soundscape right on top of us. It comes incredibly close—and this is an experience I have had on many many occasions—and when you open your eyes you are shocked by the visual distance of the sound’s source. The sound is always mediated and situated by seeing. Taking site out of the experience allows us to pull the sound as close as it always is and to give it our close attention.

Saara Hannula, one of the participants in this exercise, had this to say about her experience:

If I think of specific moments that have stayed with me, a few things come to the fore. One of them is the deep listening exercise we did by the sea, and the responses that it evoked in our group. I was very impressed by the fact that so many of us were overwhelmed by the sea and the wind when exposed to them without any protection. I wonder whether it has to do with the fact that we are hardly ever asked to surrender and open ourselves to the raw elements, or things that are beyond our understanding and control. It is quite possible to go through life without having to do it by necessity, if one happens to live in the Western world. However, I think this process of exposing oneself to the immense forces that reshape our world is key now that the situation is getting more and more out of control and the conditions are increasingly unpredictable. We can no longer resist change or pretend to manage it with the tools that we have access to. We are no longer sheltered.

I was moved by how intensely the sea was insisting on the story I heard, that we have all heard so many times before, but have not sat down and given it this kind of focus under these kinds of conditions. It is not a regular experience that you try and receive all that an experience, soundscape, has to offer, yet there is so much to learn from behaving in this way. We can get a glimpse of other time scales—geologic ones in fact—translated to our own short fragile ones. We have to be willing to slow down and give our care, openness, and attentiveness. It is deeply rewarding and taps into something we don’t do enough of because of how cut off we are from this being a regular part or our existence. We are no longer tuned to a world we evolved into, but live in a deeply impoverished terrain that serves purposes that are not in our best interests.

This text was written on the occasion of returning, a couple of days later, to the spot where we did this exercise. You can see from the images I took during this visit of just how calm everything was. There was a light breeze, barely any clouds, and when I started writing, no ripples on most of the sea. The location seemed to be less vast, daunting and emotionally overwhelming. I take this as another lesson about how we always arrive at a place with a story or metaphorical register of what it is we are encountering. I had to go stand in the chilly sea to conclude this session and to connect myself with this spot in another way.

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

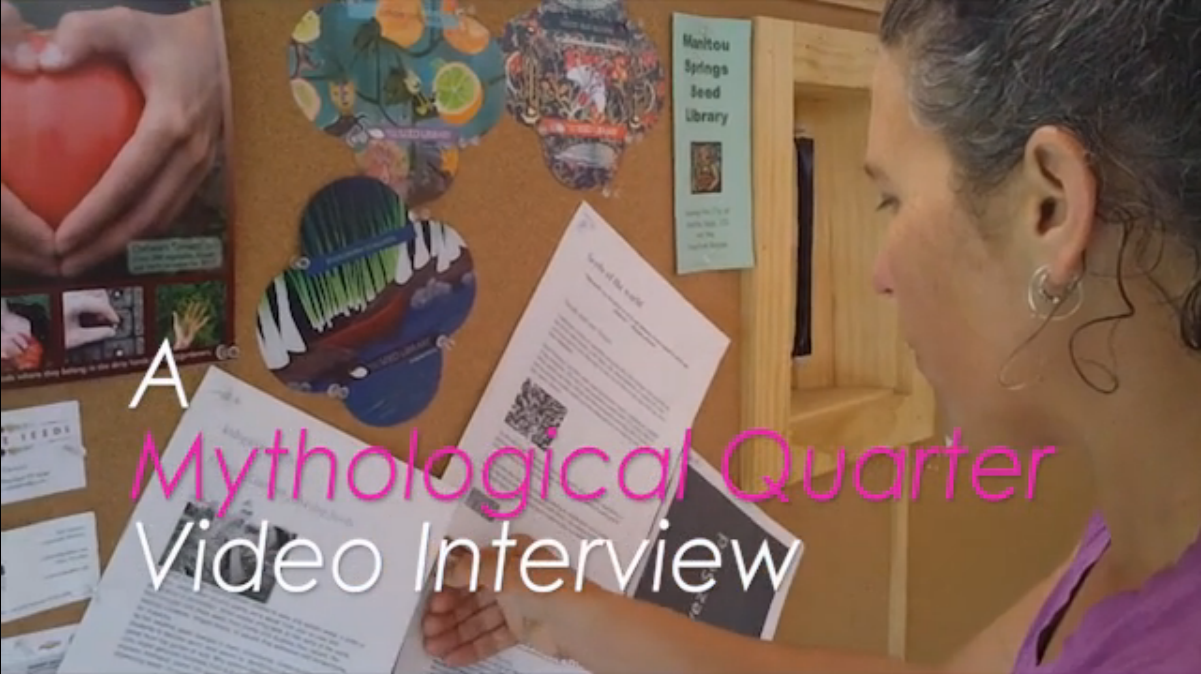

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

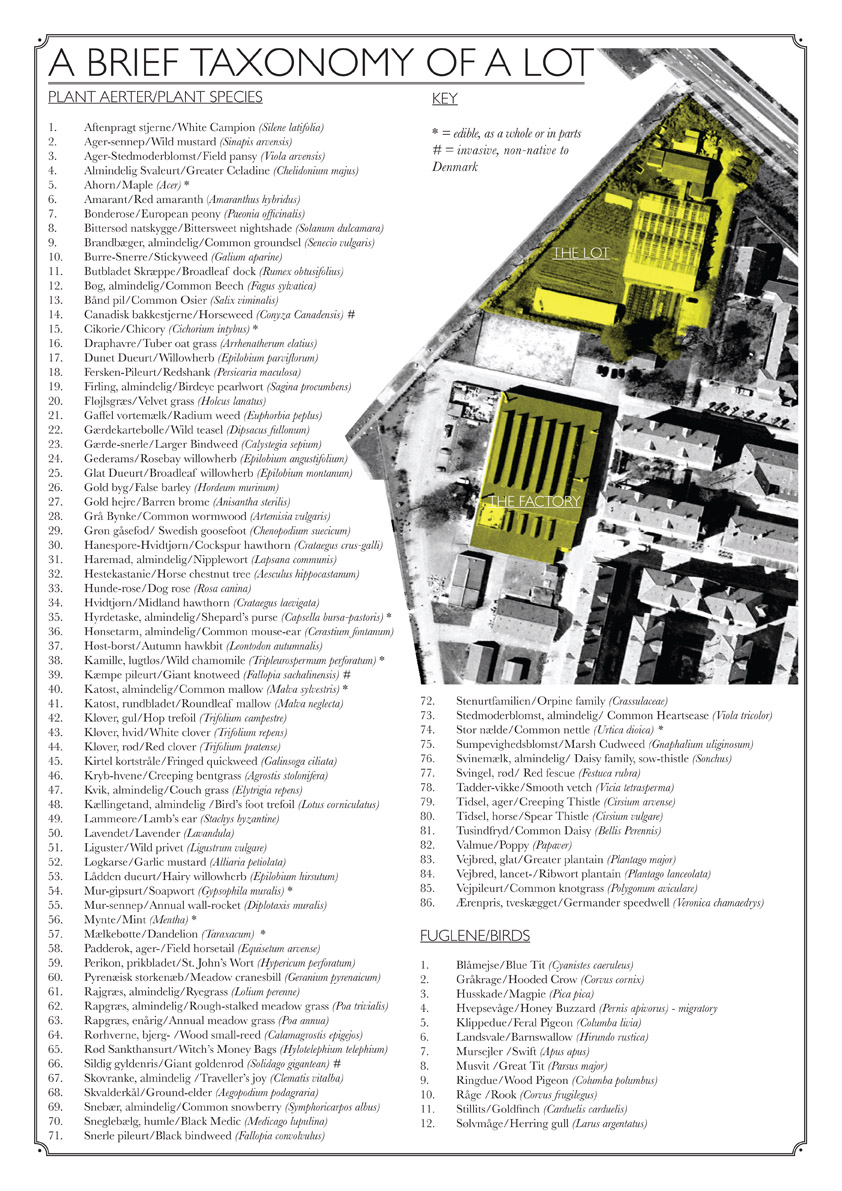

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

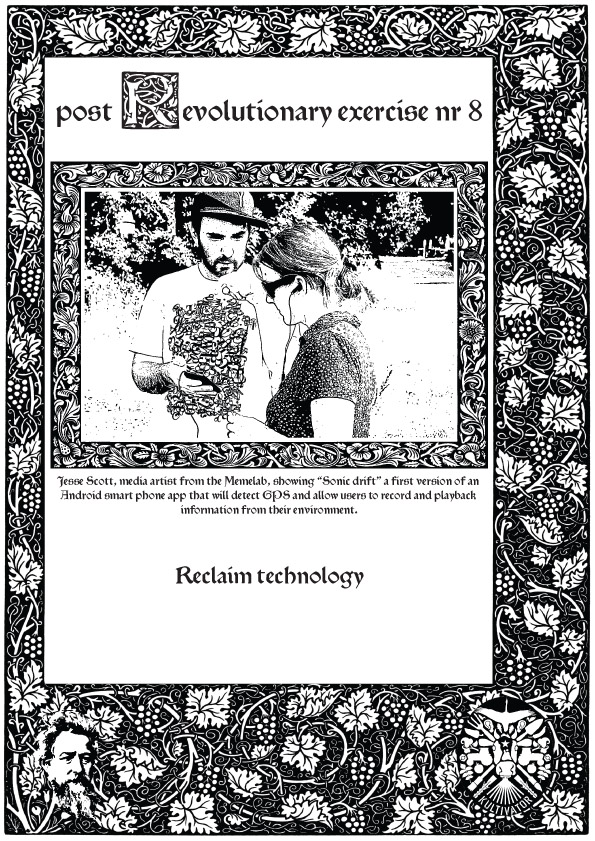

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

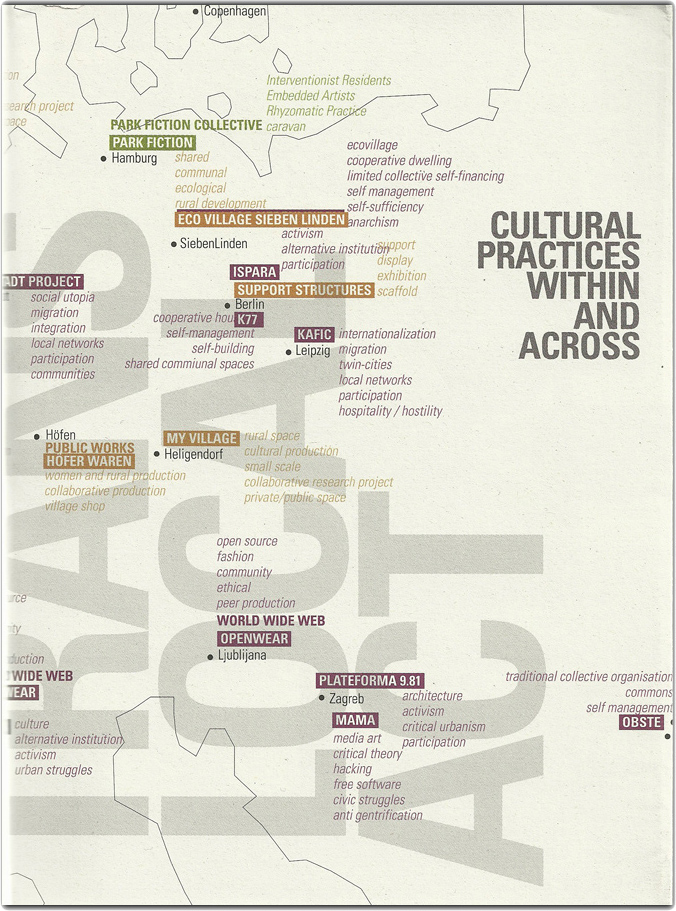

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.