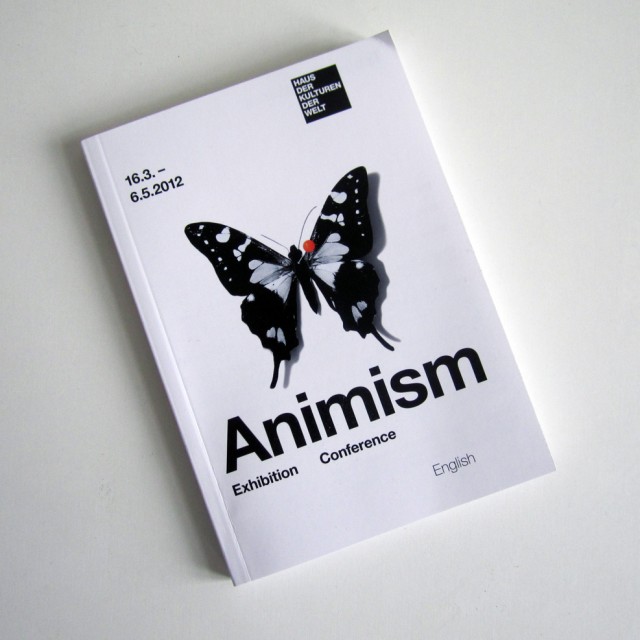

Two exhibitions: Biopolis & Animism

Last week we saw two great exhibitions dealing with the relationship between culture and nature: Animismus at Haus der Kulturen der Velt and Biopolis:Wild Berlin at the Museum für Naturkunde.

Biopolis: Wild Berlin purports to “merge the notion of biodiversity and metropolis” focusing on wildlife in the city of Berlin. This minimal exhibition, in terms of display design, relies on communicating a large amount of facts and figures surrounding urban wildlife through free standing signs. Common animals, like the red squirrel, rats, foxes, and falcons appear sporadically in taxidermy form rounding out the exhibition.

This was an exciting show for us to see right now, because it focuses so heavily on the relationship between the built environment and the wild environment. It challenges the popular conception that animals find more food and shelter in the countryside, and that they are a rare site in urban areas. There is an increasing prevalence of wildlife in close proximity to cities as the countryside evolves into an ordered, ecological wasteland devoted to industrial agriculture.

Animals find food and shelter in cities more easily relying on human waste, abandoned lots, and backyard gardens. Biopolis pointed out the inevitability of this relationship and looked at ways that people can design and plan cities accordingly. For example, many volunteer naturalists are working in Berlin to support various animals and habitat generating initiatives, including bringing back beaver populations, previously almost extinct in Germany. The Berlin municipality is also encouraging bat populations to hibernate in the city’s underground waterworks.

Berlin is especially conducive to providing habitat for wild species. According to the exhibition, support for nature is part of the city’s 800 year history. Berlin has large amounts of green space, in the form of gardens, parks, cemeteries, waterways, and woods, with less people living in the city that it was originally designed for. Everything from foxes to wild boar roam the city’s green spaces. The exhibition also mentions a new honey bee initiative in Berlin with thirteen hives being set up around the city with 50,000 bees apiece. One of these hives lives at the Museum für Naturkunde.

Animism, or Animismus in German, considers the meaning of ‘nature’ and ‘culture,’ ‘subject’ and ‘object.’ The curatorial project for Animism is a re-examining of the pre-modern cosmological practice of projecting life on to inanimate objects, and to consider it in contrast to our current basic assumptions for the order of the universe. Anselm Franke, writing in the exhibition catalog, states that animism, as a meaning making practice, is the antithesis of our contemporary, Western dualistic conception of the world ‘based on a categorical separation of subject and object.’

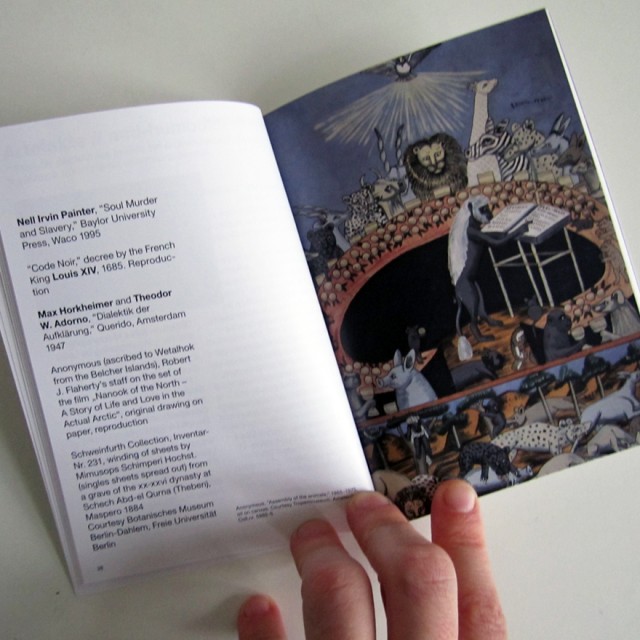

The interesting thing about Animism was its juxtaposition of, for example, an animation of dancing skeletons by Walt Disney with the ersatz geological taxonomy of ‘petrified bacon’ by Jimmie Durham. The ‘petrified bacon’ being a large, tan and brown rock resembling a piece of cooked bacon. The exhibition combined a broad range of archival and contemporary pieces together, a thrilling intellectual project that blurred many cultural and historical boundaries.

The best, and for me, most apt inclusion was Paulo Tavares film installation, Non-Human Rights (2011/2012) documenting the new Ecuadorian constitution granting legal rights to nature on the same level as human beings. This was a story we followed closely last year for its radical redefinition of fundamental rights under law. Rocks, rivers, mountains, and the like all have equal standing under this new constitution, which the exhibition catalog calls an ‘animist legal conception.’

We would desperately like to see more exhibitions like this in Copenhagen instead of vapid vanity exercises like, for example, the recent show of Bob Dylan’s paintings at Statens Museum for Kunst, or the Queen’s abysmal attempts at making art. Serious discourse that embeds art in a larger conversation is severely lacking in Denmark on both the underground and State levels.

Overall, these were two really exciting exhibitions that posit different ways of conceiving of our understanding surrounding our relationships with the natural world.

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

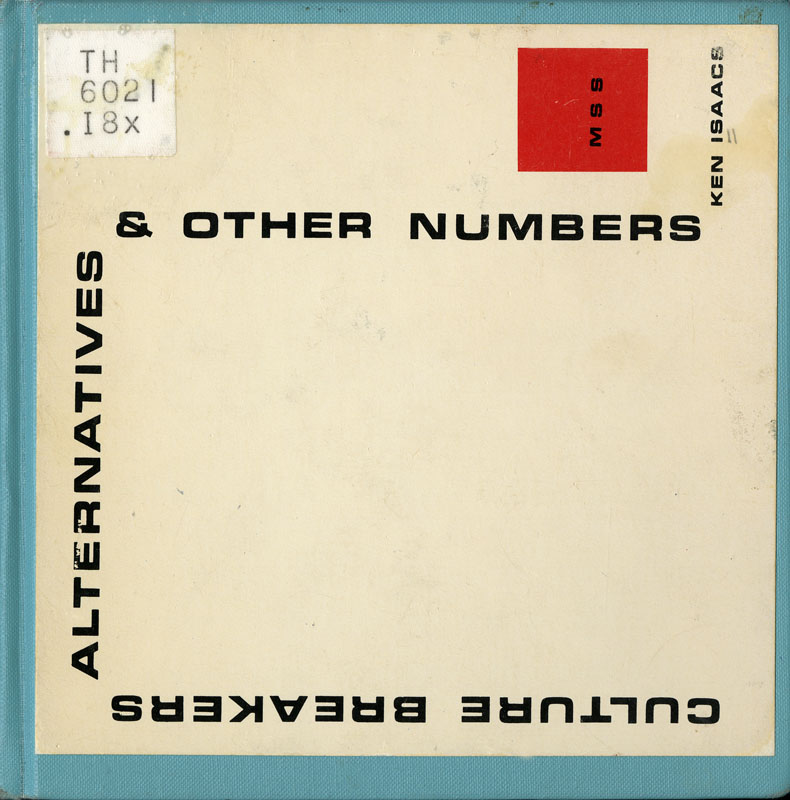

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

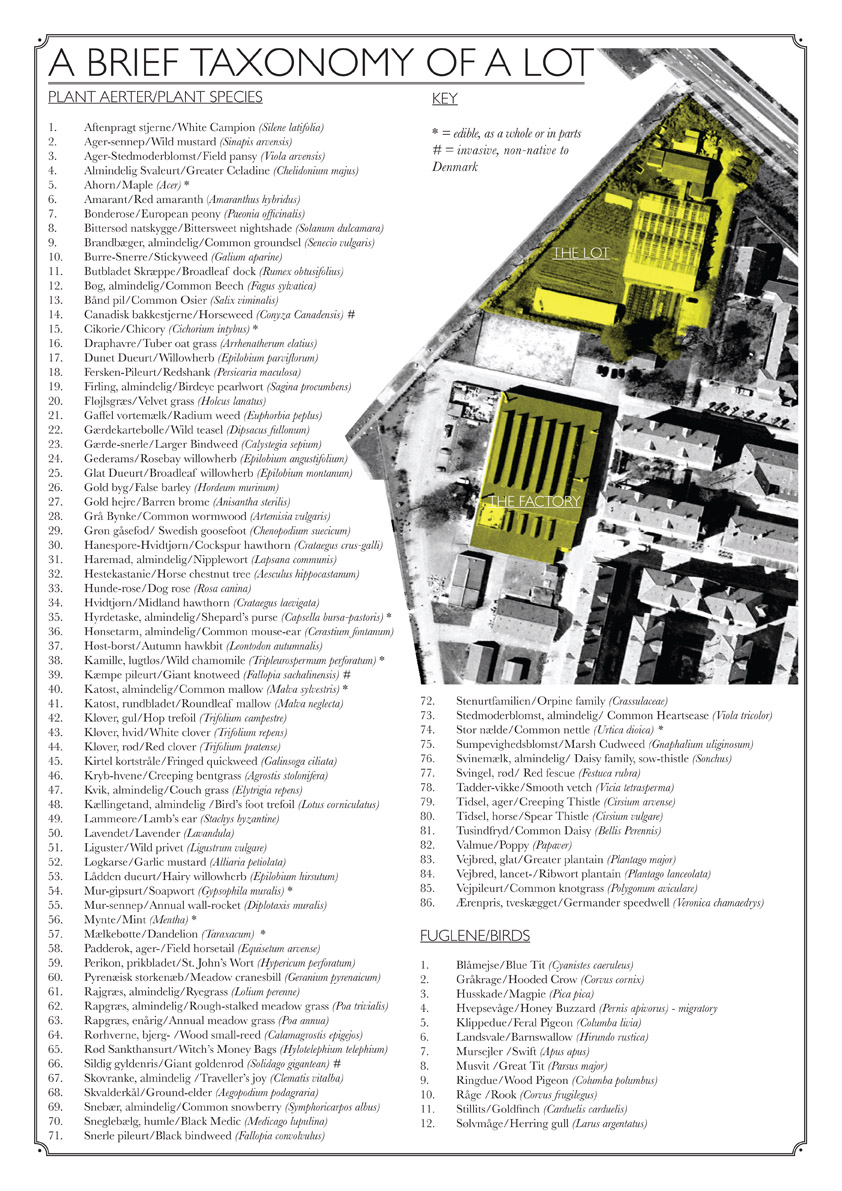

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

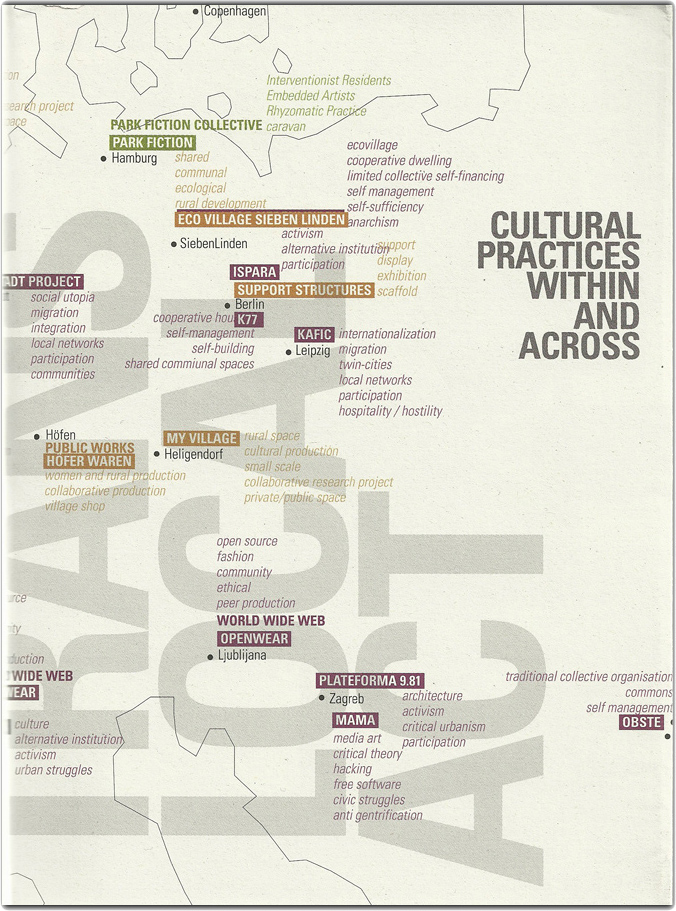

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.